I just read about the passing of Jerry Lettvin in the Spring 2012 MIT EECS Connector. I didn't know anything about him when I was at MIT 1976-1981 except that he was the funky hippie housemaster of eclectic Bexley Hall who treated us to lox and bagels, which I still eat every now and then even after I moved back to Seattle. Only in 2012 at his passing give me a chance to understand who he was and what he was about.

MIT EECS Announcement

Wednesday, May 4, 2011

Full Announcement

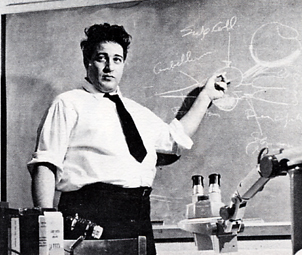

As noted in the MIT News Office, April 29 obituary, Lettvin came to MIT in 1951 under Jerry Wiesner, then-director of the Research Laboratory of Electronics, who later served as MIT president. Along with Lettvin, Wiesner also hired Walter Pitts and Warren McCulloch, creating what would become a prolific team of neurophysiology researchers. Lettvin is most noted for publication in 1959 of the paper "What the frog's eye tells the frog's brain." The paper became one of the most cited papers in the Science Citation Index. Lettvin and his team, including mathematician (and lifelong associate) Walter Pitts, Humberto Maturana, Warren McCulloch and Oliver Selfridge, demonstrated how specific neurons respond to specific features of a visual stimulus. Early skepticism on this new explanation gave way to a profound and lasting impact on the fields of neuroscience, physiology and cognition. In addition to his work on vision, Lettvin carried out many important studies of the neurophysiology of the spinal cord and information processing in nerve cell axons. Though he is best known for his work in neurology and physiology, he also published on philosophy, politics and poetry. Lettvin, popularly known as “Jerry,” was born in Chicago on Feb. 23, 1920, to Ukrainian immigrant parents. In an autobiography written for the Society for Neuroscience, he called his Humboldt Park surroundings “materially poor but culturally rich” — indeed, Lettvin had his heart set on being a poet before his mother made the “irrevocable decision” that he was to be a doctor. At MIT, Jerry Lettvin was noted for his extemporaneous speaking--most notably his debate in 1967 with Timothy Leary. Lettvin filled in at the last moment in what would become a highly publicized and later repeated set of arguments against using 'mind-bending drugs.' In Lettvin's words: "The kick is cheap. The ecstasy is cheap. And you are settling for a permanently second-rate world by the complete abrogation of the intellect." Maggie Lettvin recalled her husband's mentoring and lecturing for a history of science class at MIT: “He’d go in there and talk for three or four hours and the kids would bring their girlfriends, lunches, and just sit there forever.” He and Maggie served as housemasters of the Bexley Hall dorm in the late 1960s and early 1970s, a time that was “both enlivening and exhausting” for them, he wrote in his autobiography. He was also one of the early directors of the Concourse Program, a freshman learning community that bridges the humanities and the sciences by exploring connections between disciplines such as literature and physics, or history and mathematics. Lettvin is survived by his wife, Maggie; his three children, David, Ruth and Jonathan; and his six grandchildren. A memorial service is being planned; for more information contact Gill Pratt ’83, SM ’87, PhD ’89, a former MIT associate professor and former graduate student of Lettvin’s. Read more: MIT News Office, April 29, 2011, Emily Finn: "Jerome Lettvin, MIT professor emeritus, dies at 91. Dynamic cognitive scientist made key contributions to neurophysiology and vision science." Jerome Lettvin from Wikipedia (this picture of Jerry and Maggie from the backside is what they looked like in the 70s) http://www.improbable.com/2011/09/23/what-the-frogs-eye-tells-the-frogs-brain/  What the frog’s eye tells the frog’s brain

The memorial for Jerry Lettvin — a full day of stories, scientific talks, and maybe even some performances — happens this Sunday (September 25), at MIT, in [building/room] 32-123, starting at 9:00 am. The photo here shows Maggie and Jerry, way back when. Maggie will be at the memorial.

In case you’ve never seen it, here’s Jerry‘s most famous paper [as a downloadable PDF]: “What the Frog’s Eye Tells the Frog’s Brain,” written with Humberto Maturana, Warren McCullough, and Walter Pitts, published in 1959. It opened a giant door in research on brains — human brains as well as frog brains. Here’s a passage from near the end of it:

Of course, that’s just one side of Jerry. There are many, many, many others, including Jerry and Walter’s first published paper, a hoax that got taken seriously, and this televised duel with Timothy Leary (who, you might not realize from watching the video, was one of Jerry’s many good friends). Jerry arrives a little more than half-way into the video:

http://www.swt.org/temp/mit2005/jerry/P6040255.JPG in 2005 http://tengerresearch.com/learn/interviews/jeromelettvin.htm

(Man I must be old, because I remember these two when they were much, much younger in the 70s)

History

Jerry Lettvin worked at MIT in times when teaching and research were more flexible. He taught an afternoon class in the history of science that went on for hours because he paid no attention to the time. It was so popular that students would pack a lunch, bring their girl friends, and spend the afternoon listening to him.Jerry won acclaim for being the first person to measure the electric impulse from fine neurons. His work was published in a paper titled "What the Frog's Eye Tells the Frog's Brain" that has since become one of the most famous publications in the field.

I first met him in the 1970's when a friend and I walked into Jerry's office, unfamiliar and unannounced, and told him that we had heard that he could tell us something useful about science. The second time I saw him was in 2007, 25 years later when I spoke to him and his wife Maggie for this interview at their home outside of Boston. Afterward: Jerry Lettvin died on Saturday April 23rd, 2011.

Interview Excerpts

Read the full interview :

"I started out as a poet and became a physician, then became an electrical engineer, then a neurobiologist. It was never with any sense of searching for what people wanted to know. It was just to understand the thing that I was looking at in a way that made sense. That is a far more difficult job than writing equations…""The interesting things were the problems: were there other ways in which you could express the problem such that analogies and concordances would pop up? It’s very much like listening to music and trying to decide what is meant doing it this way rather than that way. That is essentially the way that I’ve worked all my life. I haven’t been after prizes, just curiosity, that’s all…"

"You pass out after the first two breaths… and when you wake up it is an epiphany. Things stand out with such startling clarity that you cannot quite understand how it was that such a thing as this… was… not observed… For the next 12 hours Walter (Pitts) and I were walking in a world in which every single thing became completely clear. The clarity was the likes of which you don’t experience ordinarily… It’s at this point that curiosity overwhelms you… "You see, you’re asking me how I go about things, I go about things in a way that has nothing to do with what universities teach. It’s very different from what universities tell you to do, what teachers tell you to do. You make it up as you go along, and god knows how it comes out; you don’t know… "I’m a garbage picker-upper as a mode of science: I focus on the garbage truck. I look at the parts that others choose not to pay attention to. It’s interesting the number of things that are not paid attention to... absolutely astounding…" Jerome Lettvin

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Jerome Ysroael Lettvin (February 23, 1920 – April 23, 2011) was a cognitive scientist and professor Emeritus of Electrical and Bioengineering and Communications Physiology at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). He is best known as the author of the 1959 paper, "What the frog's eye tells the frog's brain",[2] one of the most cited papers in the Science Citation Index. He wrote it along with Humberto Maturana, Warren McCulloch and Walter Pitts and in the paper they gave special thanks and mention to the work of Oliver Selfridge at MIT.[3] He carried out neurophysiological studies in the spinal cord, made the first demonstration of "feature detectors" in the visual system, and studied information processing in the terminal branches of single axons. Around 1969, he originated the term grandmother cell[4] to illustrate the logical inconsistency of the concept.

Jerome Lettvin was popularly known as "Jerry", and was the author of many published articles on subjects varying from neurology and physiology to philosophyand politics.[5] Among his many activities at MIT, he served as one of the first directors of the Concourse Program, and, along with his wife Maggie, houseparent of the Bexley dorm.

[edit]Early life

Lettvin was born February 23, 1920 in Chicago as eldest of four children (including pianist Theodore Lettvin) to Solomon and Fanny Lettvin. Trained as a neurologist and psychiatrist at the University of Illinois (B.S., M.D. 1943), he practiced medicine at the Battle of the Bulge during World War II.[6] After the war, he continued practicing neurology and researching nervous systems, partly at Boston City Hospital, and then at MIT with Walter Pitts and Warren McCulloch under Norbert Wiener.

[edit]Scientific philosophy

Lettvin considered any experiment a failure from which the experimental animal does not recover to a comfortable happy life. He was one of the very few neurophysiologists who successfully recorded pulses from unmyelinated vertebrate axons.

His main approach to scientific observation seemed to be "reductio ad absurdum"; or find the least observation that contradicts a key assumption in the proposed theory. This has led to unusual experiments being performed (some are listed below). In his best-known paper, "What the frog's eye tells the frog's brain", he took a major risk proposing feature detectors in the retina. When presenting this paper at a conference he was laughed off the stage by his peers. Yet for the next ten years this paper was the most cited paper in all of science. So a corollary approach to finding contradictions was taking risks; the bigger the risk, the likelier a new finding. This he promoted in all his students. Robert Provine quotes him as asking "If it does not change everything, why waste your time doing the study?"

He made a careful study of the work of Leibniz, discovering that he had constructed a mechanical computer in the 17th century, amongst other creations hundreds of years ahead of his time. Jerome Lettvin was also known for his friendship with the genius cognitive scientist and logician named Walter Pitts, a polymath who first showed the relationship between the philosophy of Leibniz, universal computing and "A Logical Calculus Immanent in Nervous Activity".

He continued to research the properties of nervous systems throughout his life, most recently focusing on ion dynamics in axon cytoskeleton.

He worried about how scientists approached their own work as evidenced in this playful translation he made from Morgenstern's poetry.

(This, like his other translations of Morgenstern's poems[7] from German, retains the playfulness of the originals.)

[edit]Unusual experiments

While working in the Marine Zoological Station in Naples, Italy, he had a 30-foot-long (9.1 m) room in which octopus holding tanks were kept, with fine mesh metal screens to keep them from escaping. One tank, at the far end, held his youngest son Jonathan's pet octopus named juvenile delinquent (JD).[9] One day he teased JD with a stick. The next morning, his son and he came to the door and noticed a puddle under the door. Fearing the worst (broken tanks), he opened the door, and was greeted by a blast of water in his face (but not his son's face). From across the room, and through the screen, JD had perfect aim, after which he jetted to the bottom of the tank, inked it up, and hid for the rest of the day. Still confused about the water under the door, Lettvin looked at the back of the door and saw a spot of water at the height of his face. JD had been practicing for revenge. From this and other experiences, Lettvin concluded that octopodes are highly intelligent, and from that time on he never ate octopus again, out of respect for octopodes as colleagues.

Later repeated by a pair of Russian scientists,[10] Lettvin demonstrated that a headless cat retains all of its normal functions like standing, scratching an itch, walking on a treadmill, and adjusting posture to prevent falling over.

[edit]Politics

Lettvin was a firm advocate of individual rights and heterogeneous society. His father nurtured these views with ideas from Kropotkin's book Mutual Aid. He has been expert witness in trials in both the U.S. and in Israel always on behalf of individual rights.

During the antiwar demonstrations of the 1960s he helped negotiate agreements between police and protesters, and took part in the 1968 student takeover of the MIT Student Center in support of an AWOL soldier.[11] He deplored when law is made using false science and false statistics, or when proper observations are distorted for advantage.

When the American Academy of Arts and Sciences withdrew its award of the annual Emerson-Thoreau medal from Ezra Pound for his leanings during World War II, Lettvin resigned from the academy, in which letter he wrote "It is not art that concerns you but politics, not taste but special interest, not excellence but propriety."

[edit]Debating

On May 3, 1967 [12][1][13], in the Kresge Auditorium at MIT, Lettvin debated with Timothy Leary (a licensed psychologist) about the merits and dangers of LSD.

Timothy Leary took the position that LSD is a beneficial tool in exploring consciousness and should be utilized as such. Jerome Lettvin took the position that LSD is a dangerous molecule that shouldn't be used.

He was a regular invitee at the Ig Nobel Prize ceremony as "the world's smartest man" to debate extemporaneously against groups of people on their own subjects of expertise.

[edit]Published papers

[edit]References

[edit]Further reading

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

MIT EECS - Announcement Full Announcement

www.eecs.mit.edu/cgi-bin/announcements.cgi?page=2011/data/...May 4, 2011 – Jerome Lettvin, 1920 - 2011, early pioneer in 'bio/neuro-electrical ... As noted in the MIT News Office, April 29 obituary, Lettvin came to MIT in ...MIT EECS - Announcement Full Announcement

www.eecs.mit.edu/cgi-bin/announcements.cgi?page=2011/data/...Sep 23, 2011 – Memorial Service for Jerome Lettvin, 1920 - 2011, Sunday, Sept. ... A memorial service for professor emeritus Jerome Lettvin, who died in ...Jerry Lettvin 1920 -- 2011: Jerry

jerrylettvin.blogspot.com/2011/04/jerry.htmlApr 23, 2011 – Jerry Lettvin 1920 -- 2011 ... At about 12:30 today, April 23 2011, Professor Jerome Y. Lettvin died peacefully ...http://lettvin.com/lettvin/100dpi/ ... Jerry Lettvin 1920 -- 2011: May 2011

jerrylettvin.blogspot.com/2011_05_01_archive.htmlMay 20, 2011 – Jerry Lettvin 1920 -- 2011 ... Posted by David Lettvin at 10:50 PM 0 comments ..... Jerome Y. Lettvin, Professor of Electrical Engineering and ... Images of Jerome Lettvin - Mitra Images :: Image Resources On The ...

images.mitrasites.com/jerome-lettvin.htmlStudents, colleagues, and friends ... http://jerome.lettvin.info/Jerry/wiki/index.php/Main_Page; Jerry Lettvin 1920 -- 2011. A memorial page. Please send your ...

Isaac Asimov and Jerry Lettvin

http://maggie.lettvin.com/

(This looks like it was taken in the early 70s, just a few years before I showed up in 1976)

Jerome Lettvin Videos - Mitra Videos :: Video Resources On The Net

videos.mitrasites.com/jerome-lettvin.html20+ items – List of videos about jerome lettvin collected from many ...

Lettvin Leary Debate Videos - Mitra Videos :: Video Resources On ...

videos.mitrasites.com/lettvin-leary-debate.htmlJerome Lettvin Jerome Ysroael Lettvin (born Chicago, February 23, 1920) is a ... Video Title: Timothy Leary vs Jerome Lettvin - 1/5. ... Jerry Lettvin 1920 -- 2011 ...biography of Jerome Lettvin - True Knowledge

www.trueknowledge.com/q/biography_of_jerome_lettvinJerome Lettvin, 1920 - 2011, early pioneer in 'bio/neuro-electrical engineering'. . . ... Jerome Lettvin, professor emeritus of electrical and bioengineering and .

No comments:

Post a Comment