[ Hu's on First]

Asian Americans need to decide if this election is about standing with the first Black and now Gay president who will stand up for minorities using race and gender identity as a way to get more out of government and squeeze more out of bad people with the Buffet Rule and punish guilty oppressors, and see Romney as the Whitest Guy In America. Or will Asians go back to their traditional values and value the man with a track record of making things happen, and not have to explain a lifetime of associations with people dedicated to the End Of Imperialist Capitalism.

Asian Americans need to decide if this election is about standing with the first Black and now Gay president who will stand up for minorities using race and gender identity as a way to get more out of government and squeeze more out of bad people with the Buffet Rule and punish guilty oppressors, and see Romney as the Whitest Guy In America. Or will Asians go back to their traditional values and value the man with a track record of making things happen, and not have to explain a lifetime of associations with people dedicated to the End Of Imperialist Capitalism.

Why is it that Romney and wife Ann have to apologize for being a success and coming from a successful family that doesn't have a single tie to anti-Americanism? Is it because they are the poster child of everything the left hates about America and Americans? Isn't the Romney story the dream that brought Asian immigrants to our shores, not the angry protests that Asian college protesters joined in condemning imperialism in the 60s and 70s? The media's idea of a model American story is Obama's his socialist father who pondered a 100% tax rate as fair and abandoned his mother for Harvard, his Muslim stepfather who was observant enough to drag young Barry to mosque where Barack claims he never prayed, and enrolled him as a Muslim in a school where he claims he never absorbed anything, and his mother who loved him so much, she abandoned him to pursue her PhD in third-world economics. The press dropped looking into the Black Liberation Theology preacher whose church was merely a rebranded denomination of Farakhan's notorious Nation of Islam as soon as Obama quit the last church where he regularly practiced his alleged faith, and approves of his outreach to the Muslim Brotherhood which his intelligence chief James Clapper concludes "eschew's violence" yet it shares roots with the more radical Al Queda and still works towards the destruction of Israel.

Asians need to embrace a man who will stand up for all Americans. Romney will not play this game of pitting one set of American against another. He doesn't send out spokesmen like Dan Savage who called offended Christians who walked out after being bullied by his anti-bully speech "pansies", or invite friends like Hilary Rosen to the white house who belittled wives who "never worked a day in her life". Whatever you may think of Mormonism, Romney's religion is based more on a belief in a higher power with more in common with evanglicals than the Church of Political Correctness which is the true faith of Obama and his supporters.

Here is a piece I found from the Watchers's Council that draws the stark contrast between cool and trendy Obama who embraces every politically correct trend from feminism to gay liberation to the Christian Left and the Religion of Green and the "White Square Guy" Romney. Romney evidently still believes there really was something in the wisdom of Ward Cleaver and that by following the rules we grew up we'll end up better than the rebels who believe in Better Living By Breaking Every Rule Our Parents and God Taught Us.

Bookworm on May 10 2012 at 12:08 am | Filed under: Barack Obama, Mitt Romney, Presidential elections

(reposted with permission at link above)

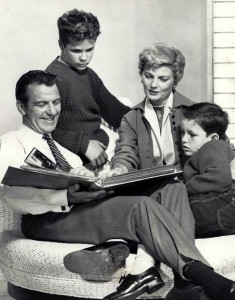

Leave It To Beaver is an iconic television show, complete with archetypal American characters. Week after week, during its Eisenhower/Kennedy heyday, the show presented its American audience with the naifs (Beaver and Wally Cleaver) being enticed into dangerous or embarrassing situations, thanks to the machinations of Eddie Haskell. Eddie was a skinny, duplicitous young man, adept at ingratiating himself with adults when called upon to do so, but basically dedicated to upsetting the placid social order prevailing amongst Beaverville’s young. When anarchy threatened, Beaver and Wally always knew that their mother, June, would express worry and dispense kisses, while their father, Ward, acting in a lovingly magisterial way, would impart wisdom, impose appropriate consequences, and generally restore sanity.

Although the show ran for only six seasons (from 1957-1963), and pre-dated the upheavals of the 1960s, it is a show that resonated in the American psyche. Generations of Americans have laughed with (and yes, sneered at) the tight little world of Beaverville, one that presented stable families; wise fathers; loving, stay-at-home mothers; and children grateful for the security that this traditional nuclear family provided.

Perhaps the scenario is a fairy tale, and never did reflect the majority of American families, but it’s a lovely fairy-tale, one that promises lasting security for the child who can escape the bad boy’s enticements and embrace the elders’ wisdom. It presents an America as we wish it would be, although we will happily accept that the next-door neighbors in this healthy, stable community represent different races, colors, and creeds, and that there’s a conservative gay couple down the block, raising an adopted orphan from China, as well as the biological child of one of the gay partners.

Simply put, Leave It To Beaver transcends race, color, creed, and sexual orientation. It is about a way of ordering the world, one that puts its trust in maturity. Further, it is a world that makes manifest the benefits of that maturity by contrasting it with the instability, physical and psychological risks, and dishonesty that naturally results from putting ones faith in a youthful hustler.

The Presidential Election of 2012 is Beaverville played out in real life, on the national stage. President Barack Obama is the skinny, duplicitous “Barry” Haskell, while Gov. Mitt Romney is the wise, affectionate “Mitt” Cleaver. Here’s a little history of the two main characters in the Eddie versus Ward show that Barry and Mitt are playing out right now, on the national stage, before an American audience:

To begin with “Barry” Haskell lies. His lying always follows the same pattern, whether he is (a) distancing himself from a troublesome priest; (b) supporting gay marriage (1996), which he did before opposing gay marriage (2004), which came before supporting gay marriage (2012); or (c) making diametrically opposite promises about Jerusalem, all within the space of a day or two. Barry’s lies are rather spectacular, in that they are peculiarly attenuated. Whenever he’s caught in a problematic situation (ah, those friends of his, whether individuals or special interest groups), rather than making a clean breast of it, or a good defense, he instead engages in a perfect storm of ever-spiraling affirmative defenses, with the common denominator always being that it’s everyone’s fault but his own.

For those who are not lawyers, let me explain what affirmative defenses are. A complaint contains allegations that the defendant committed myriad acts of wrongdoing. In response, the defendant does two things. First, he denies everything except his own name, and he’d deny that too, if he could. Next, he issues affirmative defenses, which concede the truth of the accusations, but deny that they have any legal or practical meaning.

As an example of how this plays out, imagine a complaint alleging that that the defendant smashed his car into the plaintiff’s fence, destroying it. The defendant will begin with a simple denial: Then he’ll begin an escalating series of affirmative defenses: (1) “Okay, I did bring my car into contact with the fence, but I didn’t actually hurt the fence.” (2) “Okay, I hurt the fence, but I didn’t hurt it badly enough to entitle its owner to any damages.” (3) “Okay, I destroyed the fence, but it was falling down already, so it’s really the owner’s fault, so he gets no damages.” And on and on, in a reductio ad absurdum stream of admissions and excuses.

These affirmative defense patterns have shown up with respect to some of Barry’s nastiest little pieces of personal history. When Jeremiah Wright’s sermons first surfaced, Barry denied knowing anything about them. When that denial failed, he claimed that he only had one or two exposures to this deranged level of hatred, so he didn’t make much of it. When that denial failed, he conceded that he’d heard this stuff often over the years, but wasn’t concerned about it, because he knew his pastor was a good man. (Which makes Barry either complicit in the statements or a fool.) Indeed, he even made a much-heralded speech about what a good man his pastor is. He then promised that he’d never abandon his beloved pastor. But when his pastor became dead weight, Barry dropped him so hard you could hear the thud.

The Jeremiah Wright series of lies wasn’t an isolated instance. Barry repeated this tactic when word got out about his connection with two self-admitted, unrepentant, America-hating terrorists. (That would be William Ayers and Bernadine Dohrn, for anyone out of the loop here.) When caught, Barry again engaged in a perfect storm of affirmative defenses. (1) I don’t know them. [A lie.] (2) Okay, I know them, but not well. [A lie.] (3) Okay, I know them well, but we’re just good friends, not political fellow travelers. [A lie.] (4) Okay, we’re more than just good friends, because we served on a Leftist board and I sought political advice from him. And on and on. With every exposed lie, Barry first concedes that maybe he deviated from the exact truth, and then he comes forward with a new lie.

The same pattern emerges with Rezko, with Barry freely ranging from “I didn’t know him,” to “I never took favors from him,” to “I didn’t take big favors from him,” to “I took a big favor from him, but I didn’t know it was a big favor.” It just goes ad nauseum, as if Barry is a machine, programmed to spew forth this endless flow of denial and concession. Unlike Eddie, Barry doesn’t even need a team of scriptwriters to make these lies happen. Barry is pathological in his inability to admit wrongdoing and his ability to prevaricate.

Just today, Barry repeated his pattern. In 1996, when it was politically expedient to do so, he explicitly supported gay marriage. In 2004, when Barry was making waves on the national scene, and it was no longer useful to support gay marriage, he suddenly repudiated it — with no reference to his prior position.

It’s worth noting, too, that Barry grounded his 2004 gay marriage stance in religious scripture. Today, though, Barry has apparently decided to worship at a different church, one in which Jesus pretty much mandates gay marriage. Dan Blatt, at The Gay Patriot, notes that scripture marches nicely along with Barry’s desperate need for campaign cash, some of which might come from a GLBT community that’s pleased that Barry’s finally came out of the closet on the subject. The one thing that’s for certain is that Barry has outdone John Kerry, by adding a flip to that last flop. Barry’s views aren’t e-volving, as he and his acolytes claim, they’re re-volving.

All of this is Barry’s Eddie Haskell hustle. And he does it all with Eddie’s trademarked smarminess. He knows that he’s pulling one over on the voters (they’re the Wally and Beav naifs in this national play), and he can’t resist a few winks to his complicit MSM audience. They’re all in on the joke being played on the American innocents.

Eddie Haskell also had a nasty habit of vanishing when the pot he’d stirred started boiling over. His character was the living embodiment of the old saying that, “when the going gets tough, the faux tough get going.” Barry, too, can’t stay the course. He walked out on Iraq, turning it into an Iranian satellite. He’s assured the Taliban that they need not worry about America much longer. He kicked out Mubarak, who was nominally America’s ally, and is now leaving the hapless and ignorant Egyptians to the Muslim Brotherhood’s tender mercies. Having dabbled in war’s waters in Libya, he’s decided that the Syrian people are on their own. Ten thousand or more have already died, while Barry dithers fecklessly.

Barry also shares Eddie’s behavioral dishonesty. He can turn on the smarmy charm when needed (“he oiled his way across the floor, oozing charm from every pore”), but when the pressure is on, the hustler comes out. Magisterial memorized or teleprompted speeches give way to nasty remarks about Hillary being “likeable enough,” about Sarah being a pitbull, about asses getting kicked in the Gulf States, about Americans who need to be shoved into the back seat of the nation’s figurative car, about stupid cops, etc. Just as Eddie does, Barry reserves his charm for manipulating people. He doesn’t like them; he uses them.

Also in keeping with his Eddie persona, Barry’s never held a serious job. Eddie had the excuse of being a child in an imaginary, fairly affluent suburb. Barry has no such excuse. He’s “organized,” lectured, and voted present, but the presidency is Barry’s first real job. Worse, he doesn’t seem to like the gig. Despite his savage desire to win, Barry prefers to do anything but buckle down to his day-to-day responsibilities. He wants the glory, not the sweat.

And of course, there’s the obvious physical likeness: Barry and Eddie are both young, skinny, nervous, jittery guys. Their physical presence does not inspire calm in the face of crisis.

Now, please turn your attention to “Mitt” Cleaver. He’s the grown-up in the room. Set aside the media-induced preconceptions about him being robotic, weird, and out-of-touch. You need to understand that all adolescents strive to paint authority figures in precisely that light. Doing so provides them with the justification they need to deny the adult the respect he (or she) deserves, and to ignore the wisdom that the adult has acquired over the years. (“God! My Dad is such a dork.” “Daaad! Don’t talk to my friends. You’re embarrassing me!” “God, Dad! You don’t know anything. How can you not recognize Justin Bieber?”)

Viewed objectively, Mitt is the essence of wise maturity. Not only has he held down real jobs (Bain, the SLC Olympics, Governor of Massachusetts), in each case he’s excelled, benefiting not only himself, but thousands of other people. Even if Progressives won’t admit it, and conservatives are embarrassed to admit it, capital management creates vast sums of money, not only for the money managers, but for the nation as a whole. Money isn’t trapped in dusty government coffers or doled out selectively to special interest groups in exchange for votes. It’s spread around. As Dolly Levy understood, “Money, pardon the expression, is like manure. It’s not worth a thing unless it’s spread around, encouraging young things to grow.” Romney, Bain, and that whole crew were America’s farmers, spreading that money far and wide — while pull out the weeds that appeared in the guise of mismanaged or dead-on-their-feet corporations that were trapping useful wealth.

Romney is a thoughtful man. His flip-flops lack that extra flip that Barry adds (e.g., Barry’s gay marriage flip-flop-flip). Instead, they’re the thoughtful development of ideas based upon life experience. Significantly, his changes move in one direction.

Mitt is a man of true faith, unlike Barry, who talks the talk when he needs to, but has never walked the walk. You may not like Mitt’s faith, but he’s true to it. Importantly, while its doctrine may be a bit peculiar to many Americans, the values it imparts to its followers are completely consistent with American values. Moreover, Mitt’s doctrinal beliefs don’t shift abruptly with the political winds. There’s something unstable, and downright megalomaniacal, about a man who bends Jesus to his will, rather than bending himself to Jesus’ teachings. Mitt lacks that unnerving instability.

And here’s an important one, given that Americans consistently rank Mitt’s “likeability” factor significantly lower than Barry’s. The “Barry likeability” thing is a media lie. Aside from resenting the adult in the room, the media has to sell Barry’s likeability, because it’s about all he’s got, given a record that leaves thoughtful people shuddering. Because Barry isn’t very likeable, the only way to raise Barry on that pedestal is to make sure that Mitt doesn’t get anywhere near it.

Mitt may not be the nicest man in the world — none of us know him well enough to make that call — but we do know that he’s invariably polite, that he’s capable of charm and wit, that he’s unbelievably decent (as his Bain employees will attest), and that he’s no more inarticulate than the next man (and he’s actually probably much more articulate than the next man). Keep in mind that Barry is fluent only when he’s reading words off a page. On his own, few match Barry for being completely tongue-tied (not to mention the little matter of beingignorant too, ’cause Barry has clearly studied just as hard as Eddie did).

The Eddie and Ward show culminates in November 2012. That’s when Wally and Beav, the American naifs, have to make a choice. They can continue down the “Barry” Haskell path, one that inevitably leads to lasting trouble, or they can follow the all-American Wally and the Beav, and turn to the wise parent, Papa Mitt, who is waiting in the wings to restore sanity to an increasingly insane and scary national situation.

No comments:

Post a Comment